Blog

Home

All roads lead to Rome. But I must say, this journey into topology was embarked from a pavement. Without wasting much time on my kitschy yet romantic exposition of how we got there, let’s dive in into Topology. I am mostly following the Introduction to Topology by Kinsey. Why? ’Cause my advisor told so, that’s why. I am listening to this slowed down bollywood with added rain effects (idk it’s soothing) while I do so: link.

The textbook starts with a quintessential example of turning a doughnut into a coffee cup. Wish I could also pass on all those extra calories. Topology is essentially the study of special properties of surface that are invariant to squishing, squeezing, bending, and stretching. But don’t break it, god forbid!

Two objects are topologically identical if there is a continuous deformation from one to another. In that way, it could be considered ’’rubber-sheet geometry” apparently. This topological equivalence is also referred to as being homeomorphic.

That being said, we start with the first chapter, the simpler of all, the Point-set topology.

Chapter 1: Point-set topology

The study of the most general possible object: a set of points. For now, we will constrain to the real n-space, $\mathbb R^n$.

A disc is typically used to discuss a neighborhood, but this is a misnomer. It essentially represents a $n-$dimensional sphere that is the neighborhood defined in terms of the Euclidean distance.

The interior, exterior, and boundary or limit points are determined depending on the nature of their neighborhood.

The closure $Cl(A)$ is the set of all limit points of $A$ and is a closed set.

A function $f: X\to Y$ is a homeomorphism iff it is continuous, invertible, and its inverse function $f^{-1}$ is also continuous. The spaces $X$ and $Y$ are topologically equivalent.

Topological equivalence is an equivalence relation, meaning it’s symmetric, reflexive, and transitive.

A set of points is compact if every infinite sequence of points in $A$ has a limit point in $A$.

- The real line is not compact since the sequence ${1, 2, 3, 4, \cdots}$ consists of points in $\mathbb R$ but has no limit point in $\mathbb R$. Furthermore, $(0, 1)$ is also not compact.

Intuitively and by Heine-Borel theorem, a compact set is both closed and bounded.

Accordingly, a cube is compact.

Have gone through multiple chapters in the book. Mostly these chapters were on point-set topology and connectedness, product spaces, and quotient spaces. These are not my main focus but I acknowledge that some kind of foundation on them is useful. With that said, I switch into the chapter on Surfaces.

Chapter 2: Surfaces

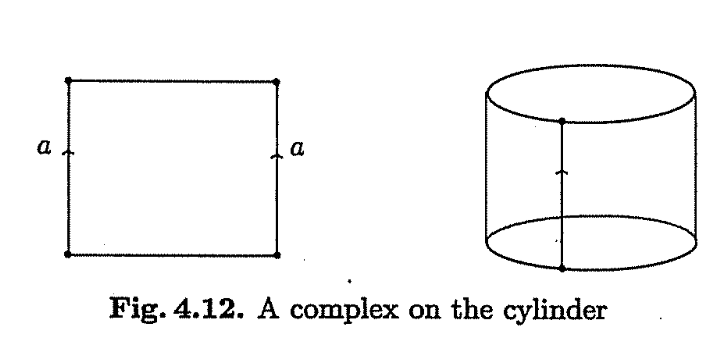

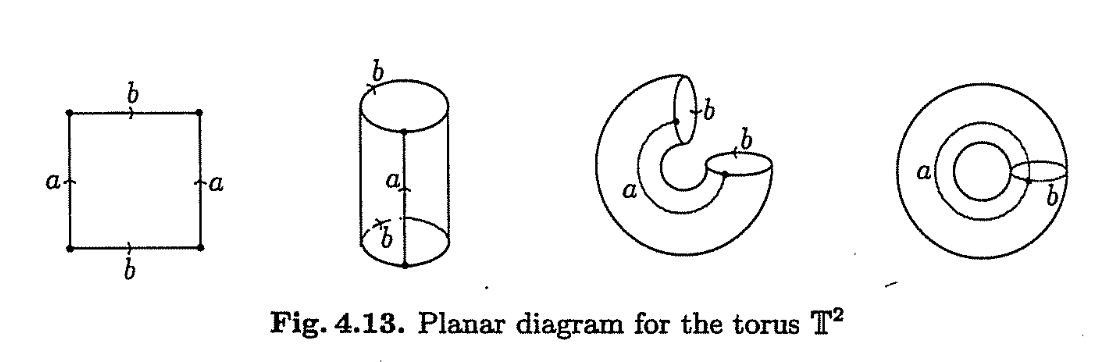

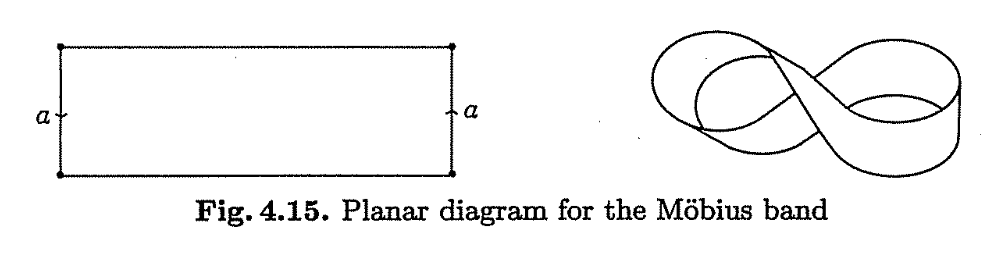

A topological complex could be constructed by glueing the similarly labeled edges together while being cognizant of the edge directions. For example, for glueing, both the edges should be in the same direction.

A cylinder can be constructed by glueing one set of opposite edges together.

A torus can be constructed by gluing both the opposite edges of a rectangle.

A disk with a zipper, i.e., both the semicircles having the same direction, is topologically equivalent to a sphere’s surface.

There are ofcourse, many different planar diagrams for any surface.

On the other hand, to represent a mobius strip, the opposite edges to be glued in the rectangle should be pointing in the opposite directions so that one of the edges have to be twisted so as to be glued to the other. The mobius strip however, has only one side, in contrast to the cylinder.

A manifold is a topological space such that every point has a neighborhood topologically equivalent to a $n-$ dimensional open disk with center $\mathbf{x}$ and radius $r$. A two-dimensional manifold is often called a surface.

This implies manifolds are Hausdorff spaces.

In classifying the surfaces, the ability to “enclose a cavity” will turn out to be a distinguishing feature.

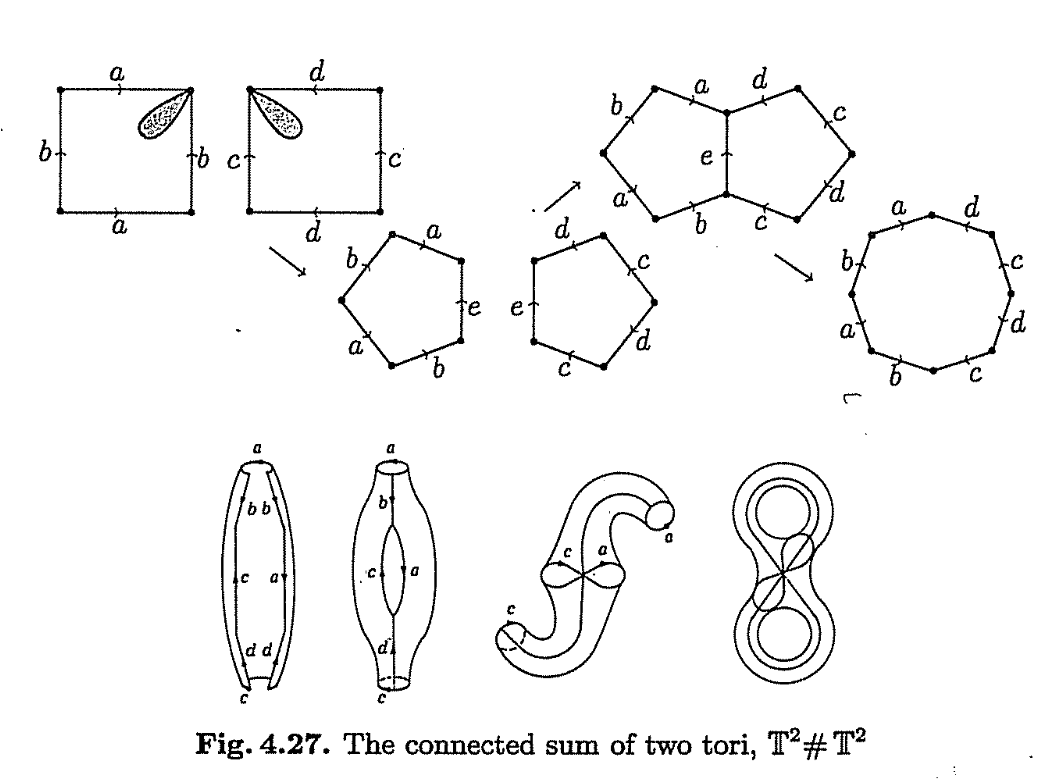

Removing two discs from two tori and gluing them together to obtain a 2-handled torus. Notice that the planar polygon for an orientable surface is a $4g$ sided polygon, given that $g$ is the genus.

While it might seem odd that for a homeomorphism, cutting is not allowed, any cut can be repaired by gluing things back just the way they were.

Classification of surfaces

Every compact connected surface is homeomorphic to a sphere, a connected sum of $n$ tori, or a connected sum of $n$ projective planes. The steps involved in classifying the surface are as follows.

Step 1: Build a planar model of the surface

Since $S$ is a compact surface, there is a simplical complex on it with finitely many triangles. Since $S$ is connected, its triangles can be rearranged so that each triangle is glued to an earlier one. Then, assemble them in the chosen order to form a polygon representing a planar diagram of the surface.

A surface is connected iff a triangulation can be re-arranged in the order $T_1, T_2, …, T_n$ such that each $T_i$ has atleast one edge common with $T_{i-1}$.

Step 2: A shortcut

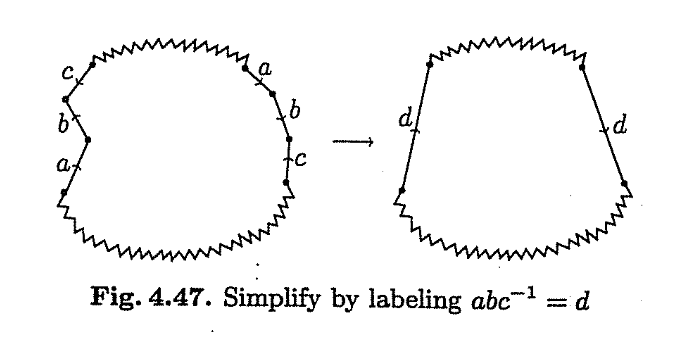

A string of edges that occur twice in exactly the same order, taking into account the directions of the edges, we can relabel to consider the string as a single edge.

Note that the edges can occur in two forms: opposing edges or twisted pairs.

Step 3: Eliminate adjacent opposing pairs

Adjacent opposing pairs can be eliminated by foldiing them in and giving them edges together.

Step 4: Eliminate all but one vertex

Step 5: Collecting twisted pairs

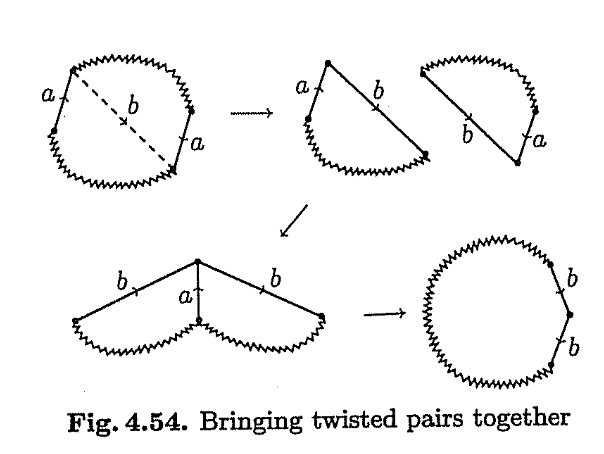

A twisted pair of edges labeled $a$ may be made adjacent by cutting along the dotted line and regluing along the original edge $a$.

Step 6: Collecting pairs of opposing pairs

If steps 1 through 5 have been performed, then any opposing pairs must occur in pairs.

Chapter 3: The Euler Characteristic

As the author quotes, ’’the obviousness of a fact never stopped mathematicians from proving it”, this chapter focuses on showing how the sphere, sum of tori, and connected sums of projective planes, are indeed really different types shapes.

Of course, the surface can be classified by creating a mind meld of cutting and pasting the surface until it is identifiable, or, perhaps, cutting it open to form a complex, triangulating the complex, and going through the process described above, to obtain an identifiable planar diagram. The first method is, at best, unreliable, while the second method is tedious.

Isn’t it better if we can perhaps come up with a characteristic of the surface that can indisputably differentiate between two surfaces. In this chapter, a simple topological invariant is introduced for exactly this purpose: the euler characteristic. This is the first step in the algebraization of topology—finding something computable to describe the shape of a space.

The information carried by the Euler’s characteristic regarding the surface is simply a number, but easy to compute. If one needs more information regarding the surface, homology theory, although difficult to compute, offers more explicit information regarding the shape of a space.

A graph, $\Gamma$, is a connected 1-complex.

Reminder: In topology, a 1-complex (also known as a 1-dimensional complex or a graph) is a topological space formed by a set of points (0-cells or vertices) and line segments (1-cells or edges) connected by those points, forming a fundamental building block for understanding higher-dimensional spaces.

A tree is a graph with no cycles.

For any graph $\Gamma$, $\chi(\Gamma) = v - e$ is the euler characteristic of $\Gamma$

Let $T$ be a tree. Then, $\chi(T)$ = 1.

Let $\Gamma$ be a graph with $n$ distinct cycles. Then, $\chi(\Gamma) = 1 - n$.

Note that adding a vertex in the middle of an edge does not change the euler characteristic.

The euler characteristic of a sphere

First, we study how much information can be gotten from the euler characteristic and then establish that it is a topological invariant.

(Def) Let $K$ be a complex. The euler characteristic of $K$ is $\chi(K) = #(0-cells) - #(1-cells) + #(2-cells) - #(3-cells) \pm \cdots$

For 2-complexes, let $f = #{faces}$, $e = #{edges}$, and $v = #{vertices}$, then the euler characteristic must be written as: $\chi(K) = v - e + f$.

Example: In a polygon with $n$ sides, the euler characteristic is $\chi(K) = n - n + 1 = 1$.

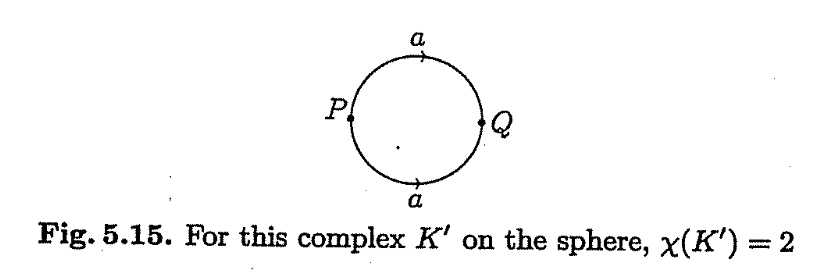

Now for a sphere $\mathbb S^2$ , the planar diagram $K’$ has 1 face, 2 vertices, and 1 edges, and therefore has an euler characteristic of $\chi(K’) = 1 - 1 + 2 = 2$

There are many different complexes that can also represent this square. Now is it possible to show that any of these complexes have the same euler characteristic?

(Theorem) Any 2-complex, $K$, such that $|K|$ is topologically equivalent to the sphere has a euler characteristic $\chi(K) = 2$.

Proof. First, we triangulate the surface into $K’$. The final remains at $\chi(K’) = 2$. First, we remove a triangle from the surface creating a hole on the sphere. This becomes a $\chi - 1$ surface. It however remains a 2-complex system. Now, start removing each triangle from the surface. There are three cases when the triangle shares, an edge, two edges, or one vertex with the boundary of the hold created. In all these cases, the $\chi$ remains the same.

Finally, only a single triangular face $\chi(K’’) = 1$ remains.

Since $\chi - 1 = 1$, $\chi = 2$.

The euler characteristic and surfaces

Euler characteristic is usually computed by means of cell decomposition. It is surprising that something so easy to compute should be a topological invariant.

Here are the ways you can perform triangulation without changing the euler characteristic.

-

Add an edge between two vertices of a polygon.

-

Add a vertex in the interior of the polygon and an edge from this vertex to a boundary vertex of the polygon.

-

Add a vertex in the interior of an edge.

Using these, we can try to perform the triangulation of a torus for example.

Chapter 4: Homology

The object of topology is the classification and description of the shape of a space up to topological equivalence.

The method described above using the euler characteristic can still be arduous and cannot differentiate the orientable or non-orientable nature of the surfaces. For example it fails to differentiate between a torus and a klein bottle, both of which have $\chi = 0$. Specifically, euler characteristic remembers to glue the edges together but ignores the direction of gluing. Homology respects these directions.

These gluing directions determine for example, that the gluing of 1-cells of a 2-complex determine whether the 2-cell forms a hollow cavity as in the inside of a torus, or not, as in the Klein bottle.

THe algebraization of topology will be a sort of layered invariant, called the homology groups, which try to express all this information.